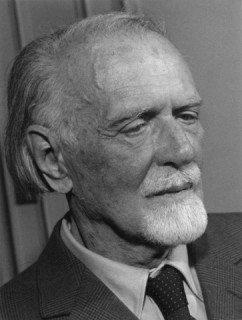

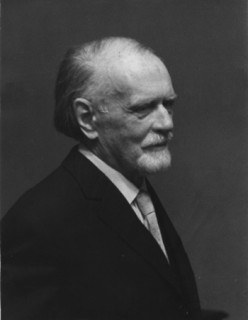

The main objective of musical education : Hungarian music culture The main objective of musical education : Hungarian music culture

Ways to reach it:

musical writing and reading should be common through schools

rousing self-awareness of musical approach

outstanding works of world literature should be public property

While Kodály was composing his concept he took a lot of examples from ancient times.

First of all if in Guido d’Arezzo’s St John’s Hymn the beginning syllables (ut, re, mi, fa sol, la) are modified and we add the 7th note (’si’ or as it is today ’ti’) we get the contemporary solmization system (do, re, mi, fa, soh, la, ti). This sort of Guido’s solmization system was later replaced or partly replaced after one hundred years by an ABC system (C, D, E, F, G, A, H). One note has got both an ABC and a solmization name, the same way it has got both tonic(relative) and absolute solfa. As its name shows the solmization notes (or tonic/relative solfa) can move, but as soon as we fix the keys, key signatures etc. and we write them as ABC notes, every note has its fixed own place. Rudolf J.Weber also used the changing of ’do’-s place in the Swiss education.

John Spencer Curwen used the solmization initials without staves for marking the pitch. Furthermore he introduced hand signals as another means to help musical education.

Emil Joseph Maurice Chevé applied the solmization notes as phasemarking. To substitute the notes he used numbers. We also use numerals in other fields of music.

we number the notes of the tune according to the grades of the scale

we count when we sing and practise intervals

singing chords when we want to mark the note distance

Chevé named the rhythms, too, but in a much more complicated way than today.

Emil Jacques-Dalcroze’s achievements are timing, clapping, knocking, - the practical application of the rhythmical elements. We use this in music schools, especially in the first years: e.g. walking at a steady pace and singing simultaneously. Dalcroze-rhythm is the basis of eurhythmics trainings with piano accompaniment.

Both Kodály’s and Leo Kestenberg’s opinions are the same:

music has to be available for everyone

teaching with music is important

the criterion of effective education is a universal and central organization

training of teachers must be in foreground

international exchange of experience is of great importance

The basis of our music education is singing - this is essential and one of the most important activities. The easiest way to music is our singing voice. Even those who play a musical instrument can imagine music easier when they sing to themselves. The basis of our music education is singing - this is essential and one of the most important activities. The easiest way to music is our singing voice. Even those who play a musical instrument can imagine music easier when they sing to themselves.

This is why mute (voiceless) singing – inner hearing – is so important, when we can imagine music before singing. There are exercises to develop this ability:

at first clapping and drumming etc. of rhythm

singing a tune from memory after observing the same tune shown by handsignals

changing parts for a signal when singing for two voices

memorizing notes on an instrument and then playing the same from memory

The next also important aspect is acquiring musical reading and writing. An old Latin proverb says, ’Tam turpe est nescire Musicam quam Literas.’ (’Not only people who cannot read are illiterate, but also those who cannot read music.’)

’Music is absolutely necessary for the development of people, this is an essential part of our education’, says Kodály. We can develop this skill already in kindergarten:

the notion of ’same’ and ’different’

the notion of ’question’ and ’answer’

recognizing and distinguishing opening and closing motives

After practising these children and later adults can improvise easily. In this way our sense of form (artistic instinct) develops and so does our general musical sense.

We recognize the elements of a harmony (intervals, scales, chords, vocal and instrumental counterpoints) as follows:

o first by singing,

o then by hearing

o and finally by the written forms.

Transposing is self-evident from the nature of tonic (relative) solfa, so is the skill in for example the clefs. So children should sing in various pitches, however, as soon as they know the ABC notes, they should sing the tune with clefs and key signatures in absolute pitch.

Writing and dictation are also important components of Kodály’s conception. “Nobody can be a good musician who doesn’t hear what he/she can see, and doesn’t see, what he/she can hear…”, said Kodály.

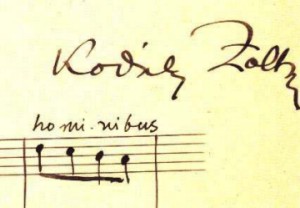

After 1945 the reform of the instrumental education also began. The vocal starting course teaches folksongs which later help students’ instrumental music learning. One of Kodály’s works – ’24 kis kánon a fekete billentyűkön’ (‘24 little canons on the black keys’) – deals with early instrumental education. He wrote several canons of one line with solmization notes and the student adds the second part singing. It trains students for very high concentration and we can make use of our earlier studies: echo-singing, rhythmic rounds/canons, memory practice, sense of form, etc. After 1945 the reform of the instrumental education also began. The vocal starting course teaches folksongs which later help students’ instrumental music learning. One of Kodály’s works – ’24 kis kánon a fekete billentyűkön’ (‘24 little canons on the black keys’) – deals with early instrumental education. He wrote several canons of one line with solmization notes and the student adds the second part singing. It trains students for very high concentration and we can make use of our earlier studies: echo-singing, rhythmic rounds/canons, memory practice, sense of form, etc.

Violin schools also make use of the students’ earlier studies. According to the tonic (relative) solfa the first 3 sounds when plucking the strings are do – re – mi (no matter which string you start on). Since the children have the clear sounding of solmization inside them, they can correct the false tunes after singing them.

This same process can be observed at schools of musical instruments, depending on the different instrumental groups. Each school starts – according to the Kodály principle – with the musical mother-tongue: folksongs. This method leans on the children’s earlier solfege studies, then these students take the further musical steps actively, together with singing – social singing and playing music. It’s a really great exercise for four-handed playing.

There are often musical competitions for students of music, they are musical reading-writing contests which were also started by Kodály. First they were only organized at the Academy of Music, then in more and more places for different age-groups. Kodály himself financed the prizes, and he made up some of the tasks himself.

Nowadays there are competitions like these at a lot of specialized secondary schools, music schools and music primary schools. With these Kodály got an overall picture of the battle against musical illiteracy. For example when anyone asked Kodály for an autograph, he only gave one to those students, who were able to sing the tune again improvised by him on the spot.

On Kodály’s advice a new type of school was founded: the song-and-music primary school where there are singing lessons every day. It has been proved that these students performed better in other lessons, TOO. Singing every day develops clear singing, sense of rhythm, spirited interpretation, the memory itself and trains students for accuracy. It refines the ability to listen for marks of tempo and dynamics and the overall comprehension. It helps emphatic readiness and lets out fantasy. The fast association and concentrated attention improve among others the sense of mathematics and feeling the musical rhythm makes better gymnasts.

At Stanford University in the USA – where Kodály also held a lecture – backward children were examined for scientific purposes based on Mary Helen Richards: Threshold to Music – which is an example for Kodály’s work adapted abroad. It turned out that those who took part in musical training had much better results, developed more than their mates who learnt with the ordinary method.

Very similarly teaching Kodály’s method at Boston and New Haven district schools for socially handicapped children of different colours it was discovered that the students hard to discipline with severe language problems showed positive and progressing tendency – thanks to the regular musical education.

|